Author Luke Longstreet Sullivan has written an astonishing memoir about the story of his father’s descent from one of the world’s top orthopedic surgeons at the Mayo Clinic to a man who is increasingly abusive, alcoholic, and insane, ultimately dying alone on the floor of a Georgia motel room. For his wife and six sons, the years prior to his death were characterized by turmoil, anger, and family dysfunction, but somehow they were also a time of real happiness for Sullivan and his brothers, full of dark humor and laughter. What follows here is content compiled by the author.

|

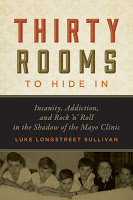

| The Longstreet family in late 1954, right after Sullivan was born. From top: Dan, Roger, Kip, Chris, Jeff, and Myra with Luke in her lap. |

“If you’re looking for proof that the Great American Family Drama is alive and kicking, here it is. Luke Longstreet Sullivan’s heart wrenching, poignant, and often hilarious family history is laid bare like a shattered bottle of bourbon. I wish more memoirs took the chances this one does. And reached such heights. This is a bravura work.”

—Peter Geye, author of Safe from the Sea

BY LUKE LONGSTREET SULLIVAN

Chair of advertising at the Savannah College of Art and Design; former resident of Rochester, MN

I began research on my book Thirty Rooms To Hide In back in the summer of 1992, the year my first son was born. At the time, all I had in mind creating was a family history; a simple transcription of all the letters and some photographs to accompany them. But over the 20 or so years since the project began, it grew and grew. After awhile I started to shrink it, perhaps to force the story back down and between the covers of a small book.

At first I had trouble deciding whether the book was about my mother or my father. For a while I thought it was about growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, about Marvel comics and the Beatles. And some days it was just about the house; about its loneliness in deep winter, its quiet in high summer. Now after years of working on the manuscript, I’m satisfied I’ve figured which one it is.

In this deleted chapter, I played with the idea that the whole sorry story of Roger’s (my father’s) life could be attributed to the fact that his Mom had ugly teeth. But it’s pure conjecture.

—–

Irene’s Ugly Teeth

I am looking at the old pictures of my father. It’s time to put them away for awhile, but perhaps one more look. There he is, my father – 9 years old in his Sunday School clothes, sitting on that stone bench. At the bottom of the picture, Grandma Irene Sullivan’s shadow, elbows out, as she holds the boxy Kodak camera. (She was cold like a rock and so we six boys named her “Grandma Rock.”)

I turn the pages and there’s a photo of Irene, not smiling as usual. In the next one she is the same, without emotion, a degree shy of a scowl. I count again the number of pictures without smiles just to make sure, and it’s true: of the 44 shots of Grandma Sullivan, only four show her smiling, and in two of those she has her hand over her mouth. In one, her smile is like a paper cut. But in the last, Grandpa Sullivan’s camera caught her off guard. It is a smile. And it is genuine.

I get out the magnifying glass to study the only photographic evidence that Grandma Rock expressed emotion and I see her teeth are, well, they’re pretty bad.

I set the glass down and wonder.

Was all this, my family’s pain and its implosion, was it caused by Irene’s ugly teeth? The theory’s at least feasible.

A Coshocton, Ohio, school girl is raised on a farm, back when there were no braces and no overnight teeth whitener. Her teeth make her self-conscious and slow to laugh, slow to smile. In middle school the boys make fun of her and in high school she stays home from dances and perhaps reads her father’s Bible, the parts about how physical beauty can’t fit through the eye of a needle on the way to heaven. She discovers no one makes fun of her at church and soon the bosom of Jesus is the place she feels most welcome. At age 31 she is saved, she thinks, from certain spinsterhood by the death of the local minister’s first wife. In her new son’s eyes she sees the boys who used to reject her: boys who were so fair playing baseball under the Ohio sun with their shirts off, boys who made faces after passing her, faces she saw reflected in the store windows. Momma tells the little boy other people can’t be trusted and the only love anyone really can count on is from Jesus.

It’s feasible.

If the explanation is not in Irene’s teeth then perhaps it’s somewhere in all these volumes of old letters here on the desk: something Mom wrote, a nugget, some incident, some detail in the police reports, something he saw in the Rorschach tests – something. I want there to be a smoking gun, an a-ha moment. Without it, I’m left only with, hey, my Dad was crazy. It’s what the doctors at Hartford said.

It makes for easy writing, but it’s not the truth.

The final answer is banal. My father got into the booze and it poisoned him and then killed him. It’s a story neither sadder nor bigger than one of those articles in back of the newspaper: “Toddler Chokes to Death on Toy.” The toy was on the floor and the baby put it in his mouth. The bottle was on the counter and Dad drank it. When he did, it made him crazy and his family suffered and he died.

I remember asking my father’s boss, Dr. Coventry, if he thought the death of Roger’s mother had anything to do with his relapse and final dissolution. The dry answer given by the Mayo scientist makes sense now: “Oh, I doubt it. There’s always something in life. You’re never going to be free of those things. No, he was simply a recidivist. He couldn’t handle his problem.”

Not a bang, but a whimper.

——-

Luke Longstreet Sullivan worked in advertising for 30 years and is now chair of the advertising department at the Savannah College of Art and Design. He is author most recently of Thirty Rooms to Hide In: Insanity, Addiction, and Rock ‘n’ Roll in the Shadow of the Mayo Clinic, and also author of of the popular advertising book Hey Whipple, Squeeze This: A Guide to Creating Great Ads. He blogs at heywhipple.com.

Find more content and photos from Thirty Rooms to Hide In (just click “Beyond the Book.”)

Sad people have to experience this, especially children… But alcohol doesn't make people crazy, it just let's you see it…